“Different paths to Independence they have trodden”: Fathers of Poland Reborn

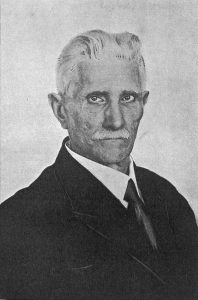

Ignacy Daszyński (public domain)

Ignacy Daszyński (1866–1936) —politician, political writer, and publicist, socialist and independence activist, co-founder of the Polish Social Democratic Party of Galicia and Cieszyn Silesia, member of the Austrian Imperial Council, Prime Minister of the Provisional People’s Government of the Republic of Poland in November 1918, one of the leaders of the Polish Socialist Party in the Second Republic, Speaker of the Sejm (1928–1930), and one of the leaders of the Centrolew movement.

Ignacy Daszyński was born on October 26, 1866 in Zbarazh,town shrouded in a mythical aura created by Sienkiewicz. There he spent his childhood, overfilled with patriotic spirit and the fairy-tale atmosphere of the January Uprising. Under the influence of his older brother, Feliks, his interests soon drifted towards socialism. Expelled from school for his paper on the events of 1848 before eventually ending up in Kraków, Daszyński traveled to Eastern Galicia, where, as a hired hand in various trades, he had the chance to take a closer look at the Galician countryside and at the fate of, the then-small, number of workers. Having arrived in Kraków in 1888, Daszyński became a student of natural sciences at the Jagiellonian University, earlier obtaining his maturity diplomain abstentia. Soon enough, however, he faced harassment and arrests for his political activity—the very same activity that in the near future would start to play a more and more serious role in the young man’s life. After a short stay in the West, where he devoted himself to studying and met Stanisław Mendelson and others, Daszyński returned to Galicia and began working intently on the development of socialist ideas. He soon became one of the main organizers of the movement and creators of socialist parties: the Social Democratic Party of Galicia and the Polish Social Democratic Party of Galicia and Cieszyn Silesia.

The political career path that Daszyński chose brought him a number of successes in politics. From 1897, he was a member of the Imperial Council in Vienna, where, as a member of the Alliance of Social Democrats’ Deputies, he became famous as a prominent speaker and polemicist. He also held the respected position of councilman of Kraków, and was an editor of the widely read and opinion-forming socialist magazine “Forward” (“Naprzód”). Before World War I, he cooperated with the Polish Socialist Party and worked closely with Józef Piłsudski, of whom he became a keen supporter, working with the “Strzelec” Sports and Gymnastic Association in Kraków and the Temporary Coordinating Commission of Confederated Independence Parties. After the outbreak of war, Daszyński became active in Piłusdski’s Polish National Organization. Nevertheless, he was still an active politician. In October 1918, he became one of the authors of the manifesto submitted to the Austrian parliament, in which the Polish deputies declared that they would henceforth consider themselves Polish citizens.

Shortly after this political display took place, on the night of November 6, 1918, Daszyński became the head of the Provisional People’s Government of the Republic of Poland based in Lublin, which announced a very progressive and democratic program of socio-economic reforms. Piłsudski, after his return to Poland, considered Daszyński to be the best candidate for the very first Prime Minister of reborn Poland, but his candidature was blocked by the National Democracy parties. From this point, focusing on parliamentary work, Daszyński became a natural leader of the Polish Socialist Party, while still a supporter of Piłsudski’s actions. This all changed after May 1926, when he became one of the leaders of the opposition to the authoritarian rule of the Piłsudski-ites. In the early ’30s, Daszynski was ailing and could no longer engage in political activities as before, although he sympathized with the Centrolew. Ignacy Daszyński died on October 31, 1936.

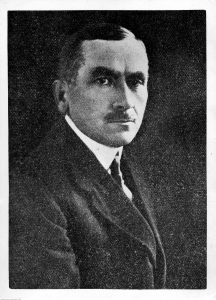

Roman Dmowski (NAC/NDA’s archive 1-A-493)

Roman Dmowski (1864–1939) —politician, political writer, and publicist; leader and ideologist of the National Democracy movement, activist of the Polish League (Liga Polska), one of the creators of the National League (Liga Narodowa), and co-creator of the National Democratic Party; member of the Russian State Duma; President of the Polish National Committee during the Great War; Polish delegate to the Paris Peace Conference; Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Second Polish Republic, among other functions; founder of the Camp of Great Poland and the National Party; and author of many political curricula and journalistic works

Roman Dmowski came into this world on August 9, 1864 in Kamionek, now part of the Praga-Południe borough in Warsaw. In spite of his initial problems at school, from an early age, Dmowski successfully combined his activism and political life with scientific activity. By the end of 1891, finishing the Russian University of Warsaw as a “Candidate of Sciences” (PhD) in the Natural Sciences, he was already a member of the Union of Polish Youth (ZET) and the Polish League. The latter transformed into the underground National League in 1893, a nationalist organization rooting for a “national awakening of the Poles,” working to increase their self-awareness in all partitioned lands. Dmowski, forced to leave the Kingdom of Poland and settle in Galicia, took over the editorial office of the “All-Polish Review” (“Przegląd Wszechpolski”) in Lviv in 1895. The name of the journal, over time, became the name for the whole movement, and Dmowski, along with Zygmunt Balicki and Jan Poplawski, became the movement’s main ideologist. Dmowski’s political works included the manifestos, “Our Patriotism” (“Nasz Patriotyzm”) and “The Thoughts of a Modern Pole” (“Myśli nowoczesnego Polaka”). Fueled by the 1905 revolution, the divergence on the “Polish Question” which was apparent in Dmowski’s and Józef Piłsudski’s factions became utterly irreconcilable. Dmowski, as the creator of the so-called “German bearing,” expressed his opinion in his famous book, “Germany, Russia, and the Polish question” (“Niemcy, Rosja i kwestia polska”). He then laid out and assumed a policy of “multiple-steps” towards the main goal: independence. Dmowski believed that the first step was to strive for the unification of the separated Polish lands. Seeing the German Reich as the main enemy of the Polish cause, he tactically aligned his political bearing with Russia, which eventually led to conflicts and schisms in the National Democracy movement.

During World War I, Dmowski led an active political life. After the successive Russian defeats, he traveled West with the hope that his actions would receive support from France and Great Britain. After the collapse of Tsarist Russia, he established the Polish National Committee in Lausanne in August 1917, which soon began to be considered by the Entente state as the sole representative of the resurgent Republic. When the war ended, Dmowski and Ignacy Paderewski represented Poland at the Paris Peace Conference. The culmination of the conference was the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919, where one can also see Dmowski’s initials.

Dmowski returned to Poland in May 1920, and soon after became a member of the Council of National Defense, which was formed due to the advancements of the Bolsheviks in their war with Poland. Still a patron of the National Democracy movement—which acted in the parliament as the Popular National Union—in October 1923, Dmowski took the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs in the coalition government of Wincenty Witos. After Józef Piłsudski’s May Coup, Roman Dmowski, faced with the new status quo and its challenges, tried to re-organize the national movement in Poland. Thanks to his initiative, in December 1926 the Camp of Great Poland was established, which, after several years, was banned by the authorities. In 1928, the Popular National Union was transformed into the National Party. Roman Dmowski died on January 2, 1939.

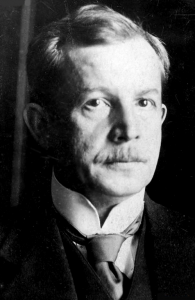

Wojciech Korfanty (public domain)

Wojciech Korfanty (1873–1939) —politician, national and independence activist, editor and publicist, publisher of the Upper Silesian magazine “Pole” (“Polak”), member of the Reichstag, Polish plebiscite commissioner in Upper Silesia, “bona fide” dictator of the third Silesian insurrection, deputy to the Sejm of the Republic of Poland and Silesian Sejm, leader of the Christian Democracy, tried and sentenced in the Brest trials, emigrant to Czechoslovakia, 1935–1939, and co-founder of the “Front Morges” opposition movement.

Wojciech Korfanty was born on April 20, 1873 in Sadzawka in Upper Silesia (present-day Siemianowice Ślaskie). Raised in a family of miners, from an early age Korfanty showed a keen interest in the cause of the Polish national rebirth on the lands of then-German Silesia. This was to be the first step towards the unification of this region with reborn Poland, in whose revival and return to the maps of Europe Korfanty deeply believed. Korfanty tried to pass on his ideas to a maximum number of his compatriots living in Upper Silesia, publishing numerous articles in newspapers edited by himself: “The Upper Silesian” (“Górnoslązak”) and “Pole” (“Polak”). In 1902, Korfanty published a series of anti-German papers, according to the authorities, for which he spent some time in prison in Wronki. Despite his imprisonment, however, he did not intend to turn back from the road he had chosen. Korfanty became increasingly involved in politics and became tied with Roman Dmowski’s national camp. While being a longtime envoy to the Reichstag, as well as the Prussian Landtag, he looked after Polish interests in those institutions. In October 1918, when German defeat in World War I was already inevitable, Korfanty appealed to the German parliament, demanding that the Polish lands which were incorporated into Prussia in the aftermath of partition decades ago be integrated into the reconstituted Republic’s area.

As a result of the decisions taken at the Paris Peace Conference, Upper Silesia’s legal affiliation was to be decided during a plebiscite, in which the inhabitants of this region had to vote in favor of either Poland or Germany. It was an obvious choice for Warsaw that the plebiscite Commissioner responsible for campaigning and agitating for Poland and taking care of the interests of the Polish population would be Korfanty. Unable to reconcile with the planned division of Upper Silesia after a plebiscite conducted in March 1921, in which fewer votes were cast for Poland, the Poles took up arms, triggering the Third Silesian Uprising. Korfanty stood up to take responsibility as its leader. Thanks to this surge and Korfanty’s effective politics, the foreign powers divided Upper Silesia in such way that the most industrialized areas of this region were ceded to Poland. Korfanty, “de facto” dictator of the uprising, has forever engraved his name in the legendary tale of Silesia’s fight for freedom and their right to Polishness.

In the Second Republic, Korfanty continued his political activities and journalism. Initially associated with national democracy spheres, in time he became the leader of the nationwide—not only Silesian—Christian Democrat movement. By 1930, as deputy to the Parliament of the Republic of Poland and outside of parliamentary debates, he remained a fierce opponent of Józef Piłsudski’s camp. In opposition to the Chief of State, plans were underway in the summer of 1922 to make Korfanty Prime Minister. Those plans, however, ultimately failed. After the May Coup and Piłsudski’s seizure of power, Korfanty continued to criticize the Marshal’s actions. In 1930, he was detained and imprisoned in the Brest fortress. Five years later, Korfanty, after emigrating to Czechoslovakia, became engaged in the “Front Morges” movement, founded by Ignacy Paderewski and General Władysław Sikorski. In the spring of 1939, Korfanty returned to Poland and was soon arrested. Released from prison due to severe illness, Wojciech Korfanty died on August 17, 1939.

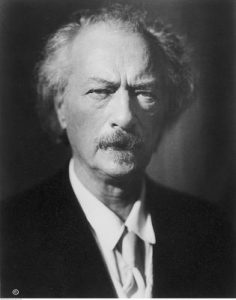

Ignacy Paderewski (NAC/NDA’s archive 1-K-6796)

Ignacy Paderewski (1860–1941) —pianist, virtuoso, composer, politician, representative of the Polish National Committee in the United States, President (PM) of the Council of Ministers and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Polish delegate to the Paris Peace Conference, co-initiator of the “Front Morges” movement in opposition to the Piłsudski-ites, chairman of the National Council of Poland during the Second World War.

Ignacy Paderewski was born on November 18, 1860 in Kuryłówka in Podolia. From an early age, he evinced musical talents, which resulted in his 1872–1878 studies at Warsaw’s Institute of Music, where he mastered piano studies. After graduation, Paderewski was hired as a lecturer at his alma mater while still developing his musical skills. Affected by a family tragedy—the death of his wife—Paderewski left Poland in 1881 and traveled west to continue his education and perfect his skills. Living in and giving concerts in cities like Berlin, Strasbourg, Paris, and London, Paderewski never stopped composing. His opera “Manru” premiered on February 14, 1902 at the famous Metropolitan Opera in New York. His international reputation made him the ambassador of the “Polish cause” around the world—a fact recognized by Paderewski and one he learned to used more frequently over time.

In 1910, funded by Paderewski, the “Monument of Grunwald” by Antoni Wiwulski was unveiled in Kraków. At the ceremony, attended by crowds of Poles from all partitions, the pianist delivered a speech, touching on the topic of the injustice of the partitions and the need to establish an independent Polish state. From that point on, politics continued to accompany Paderewski until the very end. During the First World War, he was involved, along with Henryk Sienkiewicz, in the work of the Swiss-based General Committee in Support of Victims of War in Poland. However, the greatest of Paderewski’s deeds for the independence of Poland were done on American soil. While staying in the United States and enjoying his immense popularity, Paderewski lobbied for the Polish cause thanks to his access to the administration of President Thomas Woodrow Wilson himself. It was perhaps due to Paderewski’s actions that, while giving his “Fourteen Points” address on January 8, 1918, Wilson postulated the “creation of an independent Polish state.” Since August 1917, Paderewski was associated with Roman Dmowski’s Polish National Committee, becoming his representative in the United States.

Paderewski’s return to Poland and his stay in Poznań was one of the reasons for the outbreak of the Greater Poland uprising on December 27, 1918, and his cooperation with Józef Piłsudski and assumption of the position of President of the Council of Ministers created the opportunity for an agreement between the Chief of State and the Polish National Committee in Paris. In his government, Paderewski also served as Minister of Foreign Affairs, as well as Poland’s delegate to the Paris peace conference, which ended with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. Since the end of 1919, when his government fell, Paderewski stepped away from politics, returning to music. Over time, however, he and general Władysław Sikorski became leaders of the so-called “Front Morgers” (named after Paderewski’s Swiss mansion), acting in opposition to the Piłsudski-ites. During World War II, Paderewski was considered by many to be a candidate for Poland’s President-in-exile, but he eventually became the leader of the National Council of Poland. Ignacy Paderewski died on June 29, 1941.

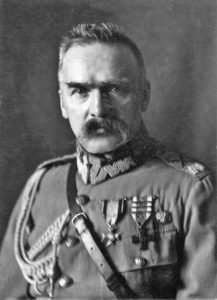

Józef Piłsudski (public domain)

Józef Piłsudski (1867–1935) — independence movement activist, first Marshal of Poland, Commander in Chief of the Polish Army, one of the creators and leaders of the Polish Socialist Party and its Combat Organization, leader of the Union of Active Struggle, Commander of the 1st Brigade of the Polish Legions during World War I, creator of the Polish Military Organization, Chief of State in the Second Republic, among other roles, Prime Minister twice after seizing power in May 1926, Minister of Military Affairs and General Inspector of the Armed Forces 1926–1935, and the actual leader of the Polish state.

Józef Piłsudski was born on December 5, 1867 in Zułów (Zalavas) in the Vilnius region to an impoverished noble family. Complicit in the plans to assassinate Tsar Alexander II, he was arrested in 1887 and sentenced to five years in Siberia. It is there that he discovered Marxist ideology and began to study it. Piłsudski treated it with a great deal of skepticism, believing that it was sometimes incompatible with Polish reality. Soon, he became a follower of “socialist nationalism” (socialism with strong patriotic and pro-independence elements). After returning from exile in 1893, Piłsudski joined the ranks of the Polish Socialist Party and he tried to lead them toward this movement. Piłsudski, while engaged with party activities, was also an editor for the magazine “Worker” (“Robotnik”) and was responsible for the distribution of so-called “blotting paper” (propaganda materials). Following the Russian Revolution of 1905, he was a keen supporter of changing PPS’s existing political profile. Piłsudski believed that the party should create a military organization under its authority, one which could either provide structural direction to an anti-Russian uprising or train cadres for the future Polish army. For this reason, Piłsudski soon became involved in the activities of the Combat Organization of the Polish Socialist Party, which was established in 1904. Intra-party differences on the “militia” issue and on the general political stance led to a schism in 1906. Piłsudski himself continued to work in Galicia since 1908. The “irredentism” camp, led by Piłsudski, had a very flexible, dogma-free policy and its main goal—independence—was to be achieved in several stages. The first step towards this goal was to take back the Polish lands from Russian rule, a country which Piłsudski considered the main enemy.

Starting in 1910, Piłsudski started expanding the activities of the Riflemen’s Associations in Galicia, which would become the base for the Polish armed forces. During the First World War, Piłsudski was in charge of those armed forces, fighting alongside Austria–Hungary and Germany as a commander of the First Brigade of the Polish Legions. In the summer of 1917, after the fall of Tsarist Russia, seeing no benefits for the Polish cause in further cooperation with Berlin and Vienna, Piłsudski led the “Oath crisis” in the Legions, which resulted in his arrest and imprisonment in the fortress of Magdeburg. Released in November 1918, he returned to Poland, where he was elected Chief of State, a post he held until December 1922.

At the same time, Piłsudski was also the head of the Polish army, commanding it during the Polish–Soviet War, where he achieved a famous victory at the Battle of Warsaw in August 1920. From mid-1923, Piłsudski devoted himself to writing and talks, avoiding the limelight of political life, while building his political background and extending his network of followers. In May 1926, Józef Piłsudski carried out a military coup, taking power in Poland. Although officially holding the positions of General Inspector of the Armed Forces and the Minister of Military Affairs, until his death Piłsudski was the “bona fide” dictator of the Polish state. Józef Piłsudski died on May 12, 1935.

Wincenty Witos (public domain)

Wincenty Witos (1874–1945), politician, activist in the independence and popular movements, co-creator of the People’s Party (Stronnictwo Ludowe) and the Polish Peasant Party “Piast” (PSL “Piast”), member of the Austrian Imperial Council, chairman of the Polish Liquidation Commission, three-time Prime Minister of the Second Polish Republic, one of the Centrolew leaders tried and sentenced in the Brest trials, a political exile in Czechoslovakia (1933–1939), German prisoner during World War II

Wincenty Witos was born into a peasant family in Wierzchosławice on January 21, 1874. From his earliest years he showed a great interest in the affairs of Galicia’s contemporary peasantry, their social status, and the social status of rural communities. Commitments to issues in his own village brought Witos to the position of village mayor, a post he held continuously from 1909 to 1931. However, his interest was not exclusively related to local issues. Witos had been a member of the People’s Party—later renamed the Polish People’s Party—catching the attention of its leaders, Jakub Bojka and Jan Stapiński. The political path he had chosen brought him several honors, including a fast track to becoming a party executive, the post of deputy to the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria in Lviv in 1908, and in 1911 the commission of deputy of the Imperial Council in Vienna. Witos not only worked towards the democratization of social relations in Galicia, the empowerment of peasants, change in the electoral system, and agricultural reform, but he also combined these issues with the need to raise awareness among the peasants as well as the issue of Poland’s independence.

The split in the people’s parties movement saw the creation of the PSL “Piast” 1914, with Witos as one of its leaders. During the Great War, the party he led did not give up the agenda for rebuilding the Polish state—an agenda specifically supported by Witos himself in a special proclamation made in May 1917 at a session of the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria in Lviv. At that time, Witos sympathized with Roman Dmowski’s national camp, and consequently decided to join the secret National League, which was set up in order to lead this political group. It came as no surprise that when the government of Ignacy Daszyński was created in Lublin on the night of November 6, 1918, Witos—due to the government’s composition, which he believed to be predominantly left-wing—did not agree to assume any position within it. However, he assumed the position of chairman of the Polish Liquidation Commission, created in Kraków at that time.

Witos’ political career gained momentum during the times of the Second Republic. The politician was widely regarded as an undisputed leader of the popular movement in Poland, and without his “Piast” party, there was no question of creating a majority in the parliament that could bring the government into existence. Indeed, Witos became Prime Minister thrice (from 1920 to 1921, in 1923 and in 1926). The establishment of his Cabinet in May 1926 in a coalition with the National Democracy party, hated by Józef Piłsudski, became one of the reasons for the coup carried out by the latter. After the May coup, Witos never regained his position in politics. Having engaged in Centrolew activities against the Piłsudski-ites, Witos was detained and imprisoned in the Brest fortress on the night of September 9, 1930. Subsequently, he was sentenced to a term of one and a half years in prison. That was when he decided to leave Poland and to emigrate to Czechoslovakia, until his return to Poland in March 1939. During the Second World War, he refused to cooperate with the Germans and was held under house arrest at his hometown of Wierzchosławice. After the end of the war, he refused to cooperate with the Soviet Union. Soon after, being gravely ill, Wincenty Witos died on October 31, 1945.

Krzysztof Kloc (Pedagogical University of Cracow).